Inland at 2,606 feet Grazalema men wore hard shoes.

They were a plain brown leather boot with four eyelets and rubber soles. Field shoes. Made for making a living in rocky fields, farming valleys and climbing mountains.

Shoes for taking care of livestock, cutting and clearing timber, shearing sheep, gathering olives, patrolling pastures and waterways, gathering stones from fields, building walls, gardening and working.

It was the same thing to them. To walk was to work. The shoes were not fancy.

Men standing around the Plaza de Espana on Sundays talking with friends in sparse January sun wore brown or black dress shoes. All dressed up and no place to go.

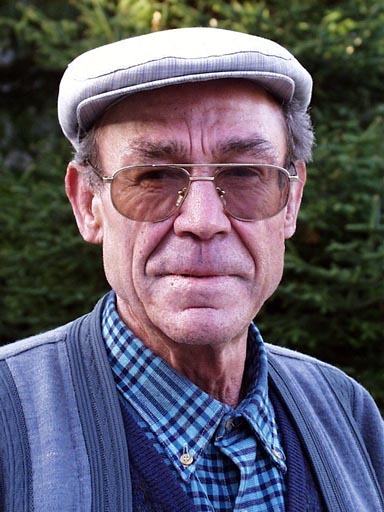

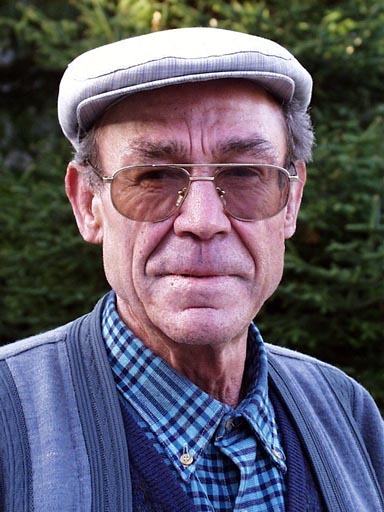

One man, a survivor of the Civil War in 1936 always wore a black beret. He taught music in a small musty dark basement room lined with empty cabinets and dusty band instruments.

His old spectacles had razor thin temples protecting hard squinty eyes and he never smiled. His gaze bore through you. He resembled a disciplined interrogation expert from Fascist Franco days. He was always dressed impeccably and wore black wing tips. There was a deep gash on the front of his right shoe where he’d met a rock.

Shoes were silent below tanned faces lined with life creases as the Penon Mountain loomed over them. Three men stood against the potable water trough staring at a white crucifix on a high mountain ridge. They talked about the weather, crops, families, politics, festivals, and pensions. Sparrows hunted for crumbs on cobblestone paths outside a cafe.

Across the plaza an old frail woman in black holding iron gratings for support sat in her open window peering up an empty street. She was a sabia, a wise woman empowered by grace and knowledge to perform magical acts.

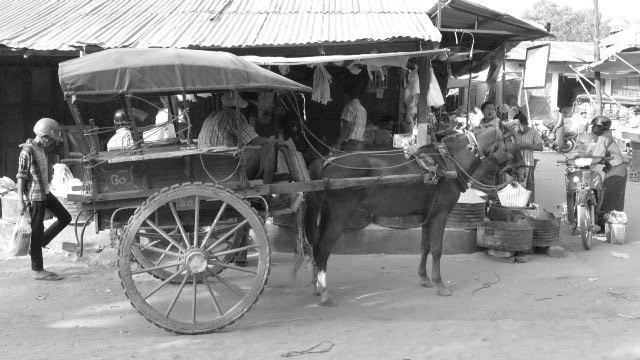

Every day at dawn laborers gathered in the Plaza de Espana Cafe for coffee, sherry, bread, ham and conversation.

“I believe because I do believe,” a man said to no one in particular gripping his hot glass of espresso.

“Believe in what?” said one rubbing his hands against winter.

“When you snap your fingers they contain instants of time,” said another.

“You gotta believe we’re going to get through this winter,” said a sad man.

Mist was thick in the valley below the pueblo. A shepherd released sheep from a pen and drove them into a field of white boulders.

Graz neighbor

A Scottish visitor sitting outside the cafe shared a story. “I taught business linguistics in college, but I’m really an amateur botanist.”

He pointed up at the Penon. “When you climb up there, as you go higher you are going back in time. You are climbing through stages of life.”

He described rare flower species in the national park and their cycle of blooming seasons at different elevations.

Hearing the botanist reminded me of Jack, a geologist in Canada in 1984 as we passed huge gray boulders along Georgian Bay and he said, “If you imagine the Empire State building and put a dime on top, the dime corresponds to human’s time on earth and the structure is the planet, specifically those boulders. They are some of the oldest stones on the planet.” Rock on.

A woman at the table said, “At everyday level, physicists believe that the arrow of time always points in the direction of increasing disorder or entropy.” Someone asked her to explain.

“The second law of thermonuclear dynamics is really simple. An easy explanation is this. If you don’t clean a room, for example, it gets messy, things get moved around. So a person expends energy to clean it up. It’s about transferring energy.”

“Thanks for the insight,” I said to the woman as she negotiated a parking ticket outside her hotel.

“You’re welcome,” she said.

Two fit English hikers passed. “Let’s go and have a little explore,” said a white-haired man to his wife.

“I love you,” she said.

A team of eighteen jubilant British hikers armed with telescopic hiking poles, laminated topographical maps, spring water, binoculars, bird books, food, and esprit de corps left the pueblo for the Sierras.

I needed a new perspective and climbed high where views past Grazalema extended east over rolling rocky fields, tilled earth, rivers, thick cork valleys and distant mountains. Vision encompassed a tiny white pueblo and microscopic humans accompanied by their shadows exploring levels of experience. I focused binoculars in cardinal directions.

One man on his sparse plot of land cleared stones by hand, put them in a wheelbarrow and pushed his load uphill near his house. He dumped stones and returned to his field of laborious love.

A man in cold shade chopped at a thick tree.

Another man used his day clearing stones and hoeing a large area for winter planting.

Sitting on the mountain peak under sky windows my calm mind savored 360 degrees of clean pure light and air.

I danced in the mysterious beauty observing geological manifestations.

“Lunch is served on the terrace,” said an invisible waiter. The main course was water, meat, cheese, bread, two bananas, and an apple. Dessert was stripping off a sweatshirt to feel sun’s heat.

A fast screaming eagle shadow zoomed over me. Zap.

Down below men renovating homes in the shadow of old Roman ruins hammered their way as children ran, yelled and played in a desperate frenzy.

Eagles and vultures soared on currents. Cloud shadows creased the valley obscuring white homes. Twilight smoke curled from chimneys.

ART - A Memoir

Adventure, Risk, Transformation

Share Article

Share Article